Air Force Falcons head coach Frank Serratore looked remarkably relaxed as he entered the expansive loading dock area on the lower concourse of the Denny Sanford Premier Center last Saturday evening. His team was just over an hour away from playing the University of Minnesota-Duluth in the NCAA Western Regional Final in Sioux Falls, S.D., with the winner getting a spot in the Frozen Four NCAA Championship in St. Paul April 4-6. Nearby the four man officiating crew were going through their own pregame warm up exercises before hitting the ice, stretching and jumping rope feverishly. As he walked past, Serratore exhorted them, “Don’t leave it all out here, guys. We’re going to need you in the third period.”

By the luck of the NCAA draw, this tournament had a distinctly Austin flavor to it. Three of the head coaches — Serratore at Air Force, Bob Motzko at St. Cloud State and Mike Hastings at Minnesota State — plus one assistant (Mike Gibbons, Motzko’s assistant, a former Austin Mavericks player on the very first team) spent considerable time living and working there, having experiences with people which shaped their personal lives and careers.

Once upon a time, he was the up-and-comer, looking up to three-time NCAA champion North Dakota coach Gino Gasparini. Now, at 60, completing his 21st season at the U.S. Air Force Academy, Serratore sits at the top of the totem pole with the younger guys chasing him. Not only is the competition formidable, he often finds himself coaching against guys he hired as assistants or who used to play for him.

Tonight’s game isn’t quite what he had hoped. Minnesota State, coached by Hastings, one of his guys whom he brought to Austin to play for the Mavericks many years ago, lost in overtime the night before to the UMD, last year’s runner-up to the national champions (Denver University). In the first game Serratore’s squad, the 16th seed of the tourney, pulled the biggest upset so far, beating the No. 1 overall seed St. Cloud State coached by his dear friends and former employees Motzko and Gibbons. Not all is lost. Tonight he can look down the bench and see Jason Herter, an assistant at UMD, whom he recruited to play at North Dakota when he worked there.

Small world this hockey business. And it just keeps on spinning.

Earlier in the week Don Lucia announced that after 19 seasons he was stepping down from his post as head coach of the Minnesota Gophers. During Serratore’s first three years in Austin, Lucia, his friend from his days growing up in Northern Minnesota, was an assistant coach at Alaska Fairbanks. On his long recruiting trips he would crash after games at his apartment just two blocks down the street from the A&W. They’d kick back at Frank’s place with a couple cold ones and discuss their aspirations for being college coaches someday.

Within a week, another coach who’d crashed at his pad, with whom he coached and hung with at summer hockey camps in Brainerd, was named to replace Lucia — Bob Motzko.

Ken Martel moved to Austin from Los Angeles to play for Serratore in his first year, graduated from Austin High, played on a national championship hockey team (Lake Superior State) and now has a cool job of his own in hockey: Technical Director of USA Hockey’s American Development Model at the federation headquarters in Colorado Springs. “Look at all the guys who either played for him or coached with him who have done well in the business,” Martell said. “There aren’t many coaches can’t who can make any claim like that.”

And it all started in Austin.

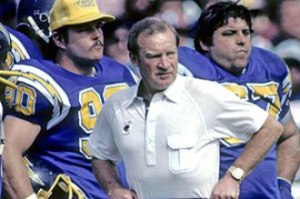

Frank Serratore

Serratore knew Austin’s Riverside Arena well. He’s played against the Austin Mavericks as a goalie for their rivals, the St. Paul Vulcans. In fact, he had a front row seat for the 1976 National Junior Finals in Austin. His netminding partner Mark Mazzoleni (later the head coach at Miami of Ohio and Harvard) started in goal in a loss the eventual champion Mavericks.

In 1982 he came as young coach looking for an opportunity. Coaches weren’t paid anything like they are now in the U.S. Hockey League, yet they were often expected to do everything from coaching to scouting to you name it. Serratore supplemented his income by substitute teaching in and around Austin.

Serratore turned the team in a perennial USHL contender. First in Austin, then continuing in 1985 when the franchise changed owners and became the Rochester Mustangs. After leaving Austin/Rochester, except for the time he was an assistant at North Dakota, he has always been a head coach.

His big break come in 1990 when he was named coach at Denver University. He hired Gibbon as an assistant and later he hired Motzko away from his buddy Mazzoleni at Miami of Ohio. Then after his fourth season, the unthinkable happened — he was fired. He never got the chance to finish the turnaround job.

He returned to Minnesota to be the general manager and coach of the Minnesota Moose, an American Hockey League team that played in downtown St. Paul at the Civic Center after the North Stars left. He got a chance at pro hockey and to add to the Serratore Coaching Tree. One of his players was a guy named Dave Hakstol, now the head coach of the National Hockey League’s Philadelphia Flyers.

In 1997 through a connection with his friend Lucia, he learned the job at the Air Force Academy was opening up. The Academy. Great reputation for discipline and academics, but when Serratore got the job they had a hard time defeating Div. III college teams let alone compete against their neighborhood rivals Colorado College and Denver University. Always known as a recruiter, he would have to use his skills to find just the right breed of bird who could fit in, to balance the academic rigors with an ability to skate and shoot and pass a puck.

“Air Force has a number of recruiting challenges other schools don’t have,” explained Brad Schlossman, for 13 years the North Dakota hockey beat writer at the Grand Forks Herald.

“They can’t recruit Canadians which can limit your pool severely. You have to find kids who excel at academics. And you have to find kids who are willing to make a post-graduate commitment.”

The No. 1 ranked cadet for the 2019 class, Kyle Haak, plays among the top six forwards on the Falcons. His major is Physics with a minor in nuclear weapons and strategy. Not many pros in the NHL (or any other sport) have that on their resume.

The core curriculum classes explain much of the academic challenge. Spread over four years, they contain a heavy dose of engineering and science — Engineering Mechanics, Computer Science, Math, Physics, Chemistry, Calculus, Astronautical Engineering, Astronautical Engineering along with four years of physical education classes. Cadets have three grade point averages, the GPA (grade point average), MPA (military point average: how you perform military drills) and the PPA (physical point average: how you perform on fitness tests throughout the year). These combine into your OPA (overall performance average), otherwise known as your class rank. Cadets get to choose their top six choices for a job when they are done at the Academy. You have to battle the competition to be eligible for your coveted job; your OPA determines where you rank in relation to the competition. It can mean whether you are flying a fighter jet, pushing the envelope like the guys in “The Right Stuff” and “Top Gun,” or sitting inside a missile silo somewhere on the prairie of North Dakota.

Among reporters who cover the Falcons, Serratore is known for his openness said Kate Shefte of the Colorado Springs Gazette. “I’ve never been turned down…His weekly press conferences can be a lot of fun, very relaxed and conversational. All the local TV stations have to do is start talking about the Vikings, and everyone’s laughing.”

Ah, yes, the post-game press conference. Many coaches fidget at the podium like they’ve just been told they’re next in line for a colonoscopy. Especially when they’re on the losing end. Serratore is one of the rare exceptions. Sometimes his pressers are just flat-out entertaining. After his team suffered a blow out 6-0 loss to Denver in which his cadets were whistled for five consecutive penalties to start the second period, he skewed the officiating crew afterwards in a way that resulted in a hit YouTube video: “Hey, there’s three things I’ve never seen in my life. I’ve never seen Bigfoot; I’ve never seen the Easter Bunny, and I’ve never seen a referee say he had a crap game.” The next game two Air Force fans, never known for being a raucous bunch, came dressed as Bigfoot and the Easter Bunny and cheered behind the bench when the Falcons came onto the ice. Seratore saw them, smiled and gave them both two thumbs up.

Under Serratore the Falcons have made the NCAA tournament and won games.The number of players they have available to them is significantly smaller, but every year they are is in the mix. He has found the right sort of player to recruit to the Academy, and the fact none of them are going to be leaving for the NHL makes the job simpler. Explained Serratore, “I’m a one-size fits all kind of guy. Every player here is on the same scholarship. All I promise them is a fair shake.”

Bob Motzko

“So who are my new neighbors?” exclaimed Jim Sack as he barged through the door of the two-story house on Second Avenue Northeast, just one block north of Queen of Angels church. Giles Motzko and his family just moved to Austin. He had three boys at the time, the oldest was his fourth grader, Bob, then Bill and Jerome (and eventually David). Jim had played hockey for the minor league Rochester Mustangs and settled in Austin after playing baseball for the Austin Packers of the Southern Minny League. The first president of the Austin Youth Hockey Association, he had a family of eight, four boys and four girls. Little did Young Bob Motzko realize it was the first recruiting visit of many he would be apart of in his lifetime.

Giles couldn’t have landed his family in a better spot. The East Side of Austin neighborhood brimmed with families with multiple children. It was another time: the mothers stayed at home, the neighbors all knew one another and the kids all played sports. Before you know it, Jim Sack had the Motzko boys signed up and playing hockey. He also had new clientele for his skate sharpening business which he ran out of his garage.

The dads developed a good friendship. Giles frequently visited Jim over at the Sack’s residence. Bob became an extended part of the Sack family, too. The Sacks had four boys — Jerry, Joe, Tony and Ed — and they all played hockey. In the Winters Bob and the Sack brothers would walk over the bridge crossing the railroad tracks to the nearest outdoor rink at East Side Lake, literally a mile-plus round trip walk through the snow and the wind and the freezing cold.

In Austin at the time every team — mites, squirts, peewees, bantams, high school — all played outdoors because there was no indoor rink. In 1973 the 2,500-seat Riverside Arena opened. A year later a group of eight investors, all local Austin businessmen, purchased a franchise in the fledgling Midwest Junior Hockey League (MJHL). They called the team the Mavericks.

Heretofore Austin had been known as a basketball and baseball town. Motzko came to Austin when hockey was on the ground floor but the sport was growing, just in time for his interest in the game to flourish. He went to Austin High, played hockey, and displayed a natural ability for

offense. “When we’d break the puck out our zone, we’d look for Bob. He would hover near center ice, waiting for a pass. He was really fast and if he had space, he was gone. That’s not to say he wasn’t a complete player, but offense was his thing,” said his boyhood friend Tony Sack.

In 1975 the Mavericks hired a new coach, a guy of Italian descent from one of the boroughs of New York City: Lou Vairo from Brooklyn. When Vairo came to Austin, he found the quintessential small-town America he’d heard about. He was the perfect guy for the job. He talked with people on the street, he taught a cooking class and he put a winning team on the ice. Motzko described him as an “unbelievable personality.” In time he was pulled into Vairo’s vortex. Vairo was an early proponent of off-ice training, having travelled to the Soviet Union to study their methods. Motzko got a chance to do some off-ice training with the Mavericks and even skated with the team on occasion. Vairo remembers he “was never out of place even though he was much younger than the team members.”

Years later, in 1987, after playing in Austin, Waterloo/Dubuque and St. Cloud State, Motzko was in Vairo’s shoes, taking the helm of a junior hockey team in Mason City, Iowa. He was the coach/general manager/chief scout/head recruiter/jersey washer/program salesman of the North Iowa Huskies in the U.S. Hockey League (USHL), a reconstituted version of the MJHL which had gone all junior (ages 17-20) since the 1979-80 season. At times it didn’t seem like it was so great; it was downright hard work. “I loved it,” Motzko said. “I was in hockey! And the hockey was really good. Most people didn’t realize what we were doing then and the impact it had. We were under the radar.”

Motzko proved he had the mettle to be a coach there when his team won the national junior championship in 1989. From Mason City Motzko moved into college hockey, getting an assistant job with Mark Mazzoleni at Miami of Ohio. In between two stints with “Mazz” at Miami, Serratore lured him out to Denver. He lasted one season before Serratore and his whole staff was shown the door. “I owe him forever, by bringing him out to Denver and then getting fired,” Serratore said.

“I’ll take it,” Motzko laughs.

In their one year together, everything that could go wrong went wrong culminating in their last game, a playoff game against Minnesota at Mariucci Arena, when their team was so decimated by injuries they could dress only 17 skaters. “Looking back, it was just a speed bump in our careers. We all went onto bigger and better things. But I learned how hard it is on families. I was single. I could pack up and leave. It’s much more difficult to uproot a family.”

Motzko spent another two years back in the grown up version of the USHL around the turn of the century. This time in Sioux Falls, South Dakota, as head coach of the Stampede. One of his toughest opponents was a member of the Serratore Coaching Tree located down Highway 29: Mike Hastings and his team, the Omaha Lancers. Hastings built a mini dynasty in his 14 seasons in Omaha, a place where all victories for Motzko seemed more like moral ones. “If we got out with a win, I was never happy, just relieved. Mike’s teams were so well prepared. Nothing ever caught them by surprise.”

Mike Hastings

His Mavericks teammates quickly took to calling him Barney, the character from the “Flintstones” cartoon. By hockey standards, Mike Hastings was undersized for defenseman. Five-foot-six… maybe. But he could play. A rink rat from Crookston, Minn., he instinctively knew how to play offense and run a power play. A smart fellow, too. Smart enough to earn an appointment to the United States Military Academy, otherwise known as West Point. He remembers his official visit: His dad was so proud. His mom was shedding tears as he got on the plane. They weren’t prepared for the news he gave them when he returned — I’m not going West Point. That’s not me.

“I wasn’t mature enough at 18 years of age to make a nine-year commitment,” Hastings said. “It’s four years of college plus a five-year military commitment. It seemed like too long a time for me.”

Hastings was content to go to college and play Div. III hockey when fate intervened. He got a call from Serratore that summer asking him to play in a hockey camp in Brainerd. Serratore recruited from hockey camps he worked there for Chuck Grillo, for years a scout in professional hockey. At the camp were several of the guys who’d played for him with the Mavericks the previous season. “Mike was a known commodity because he put up offensive numbers in high school,” Serratore said, “but he was raw defensively. You could tell he loved playing though.”

The camp was an eye-opening experience for Hastings: “I met the scariest human being in my life — Mike Castellano.” “Casto” they called him for short. A Rochester John Marshall grad, at 5-foot-11 he wasn’t terribly physically imposing, but he had a monster of a shot from the point, a gregarious personality and played with a steely-eyed meanness. His appearance contributed to his reputation. He wore black-rimmed glasses with tape around the edges. He could’ve easily passed for the long lost Hanson brother from the movie Slap Shot.

From West Point to Frank Serratore, Mike Castellano and the Austin Mavericks. Quite a change in plans. His parents bought in but on one condition — he had to continue his education. No taking time off just to play hockey. Hastings agreed to their terms. Off to Austin he went.

In late summer of 1984 the shaggy-haired kid showed up on the front stoop of the home Jed and Nancy Dudycha, big hockey fans living on the East Side with their young family. From the moment he arrived at his billeted family’s house, he fit right in. It was a perfect match. Nancy washed his clothes and cooked for him, effectively becoming a second mom. Hastings reciprocated. When he wasn’t busy doing his schoolwork at Austin Community College (now Riverland) and playing for the Mavericks, instead of going out with teammates he often hang out with the Dudychas. “If it weren’t for them, I don’t know if I would’ve made it,” Hastings said. “I was kind of a momma’s boy. They helped me get by and grow up.”

On the ice he started to flourish. When started with the Mavericks, he didn’t know how to play a one-on-one. That changed. He got to be devastating good hip checker, making the proper read and using the leverage he came by naturally to tee off on puck carriers coming through the neutral zone. “Mike was great at it. He could get a line on guys and flip them just like you’d see the pros do,” remembered Castellano.

The Mavericks won the regular season league title, lost to the St. Paul Vulcans in the play-offs, but still made it to the national tournament in Chicago. The following year Hastings returned. This time to Rochester after the Mavericks became Mustangs. Once again the team made it to the national tournament, and Hastings got an offer to play at St. Cloud State.

Hastings decision to get into the coaching profession came wrapped in a rather abrupt ending. On a road trip out East early in his sophomore year, he fractured two vertebrae in his lower back. Career over. The coach, Craig Dahl, let him keep his scholarship money on the condition he start to help the coaching staff. Thus a coach was born.

Through the lobbying efforts of Serratore and Mike Guentzel, both of whom coached the Omaha, Hastings got his big break as a head coach in 1994. He took the reigns of one of the league’s most robust franchises, winning three championships and never having a losing season in 14 seasons.

He ran into Motzko when he made a return to the USHL in Sioux Falls. Motzko’s style of team’s style of play in distinguishable, Hastings says. “Bobby’s teams have always allowed creativity; he allows them to make plays. He provides an atmosphere where talented players can flourish, but not at the expense of taking care of things defensively.”

And he added one more thing. “It’s amazing how his teams play best at the most important times. That’s a gift.”

The respect is mutual, however. “Mike is one of the premier coaches in the college game,” believes Motzko.

***

It’s amazing how prescient good coaches are. At the press conference after his team’s defeat by Air Force, Moztko said the only one way to the next opponent to beat Air Force’s was to score early, “get pucks behind their goalie” Billy Christopoulos, aka Billy the Greek, who stoned St. Cloud and made the all-tournament team. UMD did just that. They got a 2-0 lead in the first period, got an empty net goal late and hung on to win, 3-1.

Motzko didn’t see much into his own future that night; twenty-four hours later he was prepping for his interview with the University of Minnesota search committee to be the Gophers next coach. Don Lucia stepped down just a week earlier, by his own volition, he said. It was time for the next guy. Better a year early than running out of gas, having to get one more win or one more tournament appearance to keep your job. At the press conference announcing his departure, Lucia quoted his good friend “old Frank Serratore” from an earlier conversation they’d had at Serratore’s house about how it could be possible to leave Minnesota: “He (Frank) says they got a lot of blank-you money and at some point in time if they don’t want you, they say ‘blank-you,’ write you a check and you’re outta there.”

In the next Minnesota presser announcing the new guy’s arrival, Motzko told the assembled crowd Serratore’s thoughts on his qualifications for the Gophers job: “Frank said nobody deserves this job more than Bob Motzko since Brad Beutow cut you twice.”

Motzko assured everyone he wouldn’t be at Minnesota as long as Lucia. Most coaches don’t the choice to end things on their own terms. Hastings’s formula for when to stay and when to go comes down to a few honest questions: Are you still relevant to your players? Are you still passionate? Do you can about it like you did when you started?

Serratore refuses to put on expiration date on his own coaching career. “If it gets to the point where I’m not enjoying it or my school doesn’t want me anymore, I’m done.”

-30-